How Recent Changes to SBA Loan Requirements May Affect Self-Storage Borrowers

Recent changes to Small Business Administration (SBA) loan requirements will affect some self-storage borrowers. Learn when SBA funding still works and an alternative financing source to explore when it doesn’t.

The Small Business Administration 7(a) and 504 loan programs have proven to be reliable, go-to funding sources for self-storage owners and developers looking to build, buy or refinance. Hundreds of millions of dollars have flowed to storage operators since the Great Recession and during the extended market expansion that followed. Earlier this year, however, the SBA updated its standard operating procedure (SOP) to include new restrictions for businesses that use third-party management companies. This change has proven to be an obstacle for some seeking SBA financing. Thankfully, there are alternatives.

Factors like ongoing capitalization-rate compression, a growing population, and changing cultural and societal trends—not to mention an abundance of construction, acquisition, rehab and refinance capital—means an institutional or private owner looking to purchase or refinance stabilized or in-transition properties can take advantage of short and long-term non-recourse financing through the commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) market and other alternative sources. Let’s look at when SBA funding still works and a suitable option to consider when it doesn’t.

SBA Programs

First, let’s do a quick review of SBA loan programs. Under 7(a), a bank typically makes a loan of up to $5 million, and the SBA provides the institution with a 75 percent guaranty. In some instances, lenders have made larger loans using a “pari passu” structure in which the mortgage is shared between a $5 million 7(a) loan and a conventional loan. Banks can also reduce their guaranty percentage to allow for a larger loan, but this is unusual.

Typically, because a portion of their risk is mitigated, banks are willing to structure and price SBA loans more aggressively than they would conventional loans. This equates to higher leverage and longer terms for borrowers. Under the most common structure, a bank will lend up to 85 percent of the value of the property. In this case, funds can be used to purchase land, for hard and soft construction costs, FF&E (movable furniture, fixtures or other equipment), construction/post-construction interest reserves, and lease-up working capital to fund operating expenses until stabilization is reached.

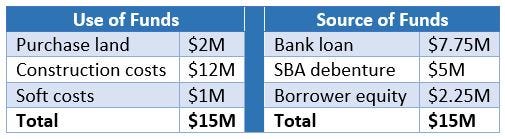

Under a 504 loan, rather than all the money coming from the bank, borrowers receive up to 40 percent of their capital stack through a “debenture,” which is effectively a bond sale backed by the U.S. Treasury. This debenture is paired with a bank loan to cover 50 percent (or more) of the project. Together, the loans accommodate up to 90 percent financing. While the SBA’s piece is typically capped at $5 million (some renewable-energy installations can qualify for up to $5.5 million), the bank piece has no limit. This makes 504 loans a viable option for large projects, such as the one detailed in the following table.

In contrast to the 7(a) program in which banks typically structure their loans with a floating rate pegged to Prime, the SBA debenture on a 504 is always a 20-year fixed rate, and banks usually fix their loan for at least five years. The end product is long-term, fixed-rate financing at attractive rates. However, while post-construction interest reserve and working capital are eligible to be financed within 7(a), these are classified as an “ineligible” use of funds under the 504. As a result, owners must ensure they have adequate post-injection liquidity to fund debt service and operating expenses until the property achieves stabilization.

Another subtle but important distinction is 504 loans undergo far more scrutiny than 7(a) during underwriting. This is because all 504 loans pass through a California-based centralized processor known as the Sacramento Loan Processing Center, which can be notoriously stringent and unpredictable during application review. In contrast, the 7(a) program is largely dominated by banks that are designated as preferred lenders, giving them delegated authority to underwrite, approve and fund applications without going through a processing center.

Wading through the pros and cons of either program can be tricky. An experienced intermediary or investment banker can provide valuable guidance in navigating the decision-making and transaction processes.

How the SOP Applies to Self-Storage

Released earlier this year, SOP 50 10 (J) includes new regulations for borrowers that use third-party management companies, as many self-storage owners do. In the past, the SBA allowed operators and third-party firms to engage in property-management agreements with only cursory oversight. The new SOP, however, spells out specific requirements that must be outlined in any management contract. Under the new rules, SBA borrowers must:

Approve the annual operating budget

Approve any capital expenditures or operating expenses over a significant dollar threshold

Have control over the bank accounts

Have oversight over the employees operating the business (who must be employees of the applicant business)

The last clause is italicized because it’s the most subtle and important point for self-storage owners using third-party managers. When the SBA says staff must be employees of the applicant business, it’s referring to the borrower. In other words, facility staff cannot be employees of the management company.

This has serious implications for the relationship between the self-storage owner and management company, and it’ll take time for the big firms and their legal teams to reconcile this requirement and make it work. Lenders will likely find creative ways to make these deals while the market digests and works through these new requirements. In the meantime, though, expect considerably tougher sledding when seeking an SBA loan if your plan includes third-party management.

An Alternative Option

Thankfully, the conduit loan market, in which lenders pool loans and sell them on the secondary market as CMBS, remains very robust and reliable for long-term fixed rates. A typical structure involves a 10-year fixed rate and 30-year amortization, with rates ranging from 2.15 percent to 3 percent over the 10-Year Swap Rate, depending on the leverage point, in-place cash flow and asset location. As an added benefit, these loans are typically non-recourse without the burden of personal guaranties. This means only the property is on the line to satisfy the loan.

Not only does a non-recourse loan insulate owners from unnecessary personal risk, it keeps the personal balance sheet clear, allowing owners to take on more debt for other properties. With conduit loans, leverage is typically capped at 70 percent, with higher leverage available in certain instances. Any equity freed up as cash-out at closing (in the case of a refinance) is typically disbursed tax-free, with no limits or strings attached (please consult your tax adviser).

Using a Combination

A common business model is to use the leverage afforded through the SBA programs to construct or acquire an asset, followed by refinancing with a conduit loan once the property stabilizes to take advantage of the long-term fixed rates, cash-out availability and non-recourse. Notably, a good portion of conduit lenders are also willing to make 10-year, fixed-rate loans with 30-year amortizations to self-storage owners for amounts as low as $1.5 million. This is a significant advantage over the $3 million lending threshold for other asset classes and demonstrates lenders’ affinity for storage projects.

When buying or refinancing a value-add property, conduit lenders also offer short-term bridge loans. With these, the leverage is based on the projected value of the stabilized facility, so owners can obtain non-recourse loans even if a property is still in transition. This strategy buys time to execute your business plan before selling or refinancing to permanent debt.

This is just a small snapshot of the financing readily available to self-storage owners and investors. Your choice should be driven by your short- and long-term goals and priorities. Working with a skilled intermediary who knows the nuances, market, asset class and, most important, the lenders, can significantly increase your options, eliminate obstacles and improve the final results.

Mac Dobson is senior vice president at Mag Mile Capital, a Chicago-based commercial mortgage and real estate investment banking firm that offers debt placement, equity arrangement, tax-credit syndication, real estate brokerage and advisory services. To reach him, call 734.604.6962; e-mail [email protected]; visit www.magmilecapital.com.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like