With the federal, state and local governments issuing restrictive orders in response to the coronavirus, it can be difficult to know which rules to follow. Get a legal opinion on how they apply to self-storage operations.

With so much happening around the coronavirus pandemic, it’s tough to keep up. As the federal, state and local governments issue orders and restrictions, self-storage operators may need clarification on ambiguous language and mixed messaging. Among the most pressing concerns is what constitutes an “essential business” and whether storage facilities should stay open. If your facility is open, what rights do you have as landlord against tenants who fail to pay rent?

As I write this, we’ve already witnessed the first wave of “shelter-in-place” orders; but with the difficulties faced by the unemployed to pay mortgages or rent, lawmakers are starting to issue amended orders that address a landlord’s ability to charge late fees, restrict property access and evict. This second wave of controls challenges landlords of all types to wonder, “If my tenants aren’t paying me, how can I pay my lender, taxes or utility bills?” Let’s take a closer look.

Essential Business

There isn’t one convenient answer to the question of whether a self-storage facility is an essential business. If a state or local order references the current (March 28) version of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s identification of essential, critical infrastructure workers, you won’t see “self-storage” on the list (remember warehousing is specifically not self-storage). However, you’ll see that people who work at vehicle-leasing agencies (truck rentals) are permitted as well as any business that handles mail delivery (mailbox rentals).

In addition, many state and local orders permit businesses to remain open to allow access to necessary supplies and services for household consumption and use; supplies and equipment needed to work from home; and products needed to maintain safety, sanitation and essential maintenance of a home or residence. Thus, it’s possible someone may need to get into his self-storage unit to get supplies for his family, and the facility would need to allow that person access.

Many of these orders also allow for “minimum basic operations,” permitting a company to maintain the value of its business, manage inventory, ensure security, process payroll and employee benefits, and handle related functions. Based on these many “exceptions,” most self-storage operators have dropped to skeleton crews and closed offices, allowing tenants to visit units only through gate-access systems and shifting new rentals and payments online to manage new customers or close current accounts.

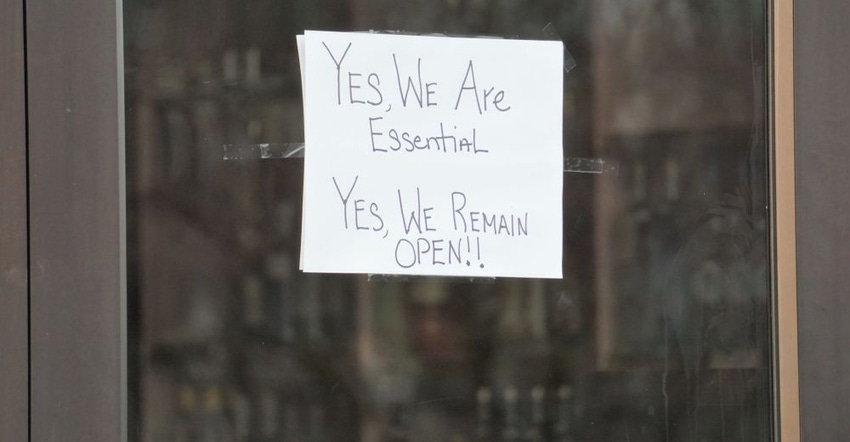

Since local law enforcement may impose different interpretations of the various orders, the current solution for self-storage operators in shelter-in-place states would be to close the office to the public (you could allow an employee to remain in the office), allow gate access for customers, and place language on your gate and website indicating the facility is open for “essential services use only.”

Late Charges, Overlocks and Lien Enforcement

When it comes to assessing these important operational procedures, it’s probably easiest to start with the conclusion and issue this general warning: To the extent your state or local law has denied any evictions from proceeding, the legislative message is likely that any enforcement action against a tenant (residential or commercial) is also prohibited. While orders may not have specifically included non-judicial foreclosures like self-storage lien sales, the restrictions on gatherings of more than five or 10 people, coupled with the limitation on tenants to travel due to stay-in-place orders, may be a potential defense as to why a tenant wasn’t able to exercise his right of redemption before a lien sale could occur. I believe this is why most operators decided to put a stay on lien sales, at least until the orders are lifted.

Now, whether a facility operator must waive his contractual late fees for non-payment or forego the exercise of his contractual denial of access to a delinquent tenant is an entirely different issue. Though you wouldn’t normally be barred from enforcing your contractual rights, we’re seeing a number of states impose limitations on a landlord’s right to deny access to defaulting tenants or even to charge late fees. Since these laws are growing in number, it may be best to waive late fees and forego the use of overlocks for now.

That said, there’s no bar or governmental order that waives a tenant’s obligation to pay rent. Essentially, the current executive orders simply stay the collection of certain rent obligations (mostly residential). Again, the intent of these orders appears to be to give tenants an opportunity to avoid the loss of their property due to non-payment. Some impose an obligation on tenants to provide proof that the reason they’re unable to pay is connected to the pandemic, such as loss of a job. In consideration of waiving fees in states that don’t have a specific requirement to do so, it isn’t unreasonable to inquire why a tenant has failed to pay rent.

Read Carefully

The ultimate message here is to carefully read the specific orders that have been issued in your city, county and state. Where conflicts between orders exist, many states proclaim the state order governs over any inconsistencies or omissions that might appear in municipal orders.

Further, if you have any question concerning the applicability of your particular governmental order, you have the right to request clarification from the governor’s office. Be prepared, however, for it to sway against your business as essential as well as against your ability to enforce contractual remedies.

Under the circumstances, support will fall to the consumer or tenant and against the landlord. The philosophy within government orders is to avoid anyone having to be involved in commerce unless it’s essential and to eschew defaults where they can be circumvented. The announced goal to “flatten the curve” extends beyond the spread of the virus and applies to minimizing the financial impact on consumers and the economy.

Note: This article was originally published in the author’s “Legal Monthly Minute” Newsletter.

Scott I. Zucker is a founding partner in the Atlanta law firm of Weissmann Zucker Euster Morochnik & Garber P.C. and has been practicing law since 1987. He represents self-storage owners and managers throughout the country on legal matters including property development, facility construction, lease preparation, employment policies and tenant-claims defense. He also provides, on a consulting basis, advice to self-storage companies in the areas of foreclosure and lien sales, premises liability, and loss-control safeguards. To reach him, call 404.364.4626; e-mail [email protected].

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like